I first wrote parts of this essay about my National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) horsepacking course experience for the academic portion of my class enrollment at Western Colorado University.

It has been adapted for Wandering Home as a contemplative account of my time in Wyoming’s Absaroka Mountains from August 23–September 4, 2020.

Growing up, my family’s rallying cry was something like be careful. Our anthem: be safe.

I lost a teenage brother to a car accident when I was very young, and at the same time, missed the chance to grow up with an older sister who was raised by her mother rather than our shared father. I was raised by parents who had lost children and did their best to protect the younger of us. I knew I was safe and loved. Even so, within my young mind I decided to try to fill a secret void, to be “good enough” for my family who’d lost a lot.

We know how subjective remembering our childhoods can be.

As so many of us do, I picked up early on that vulnerability wasn’t ideal, and being strong and impenetrable was how you got through life. It makes sense. I mean, look at what we’d been through.

I suspect it was the perfect storm of influential nurturing, or being raised as the oldest while being a perfectionist, and then teenage years of nights I can’t remember that made me reconsider this approach in my twenties.

I graduated from college, was married (into the military life, no less), and moved to Texas all within two weeks. Within a month, my husband deployed to the Middle East and left me alone in a city where I knew no one, without a partner, a job, or, honestly, a life.

That’s one way to learn about vulnerability.

_____

A decade later, I try to be a student of vulnerability by working to examine and rectify a lifelong inflated desire for security, safety, and being enough. Not long ago, that took the shape of Cougar Pass on horseback.

The wind whipped violently. We had to yell to be heard more than single horse-length ahead of us. I had my windbreaker zipped over my chin, damp from condensation and chafing from the rocking and swaying as we approached the top of the pass. Buttermilk, my horse, let out dramatic huffs as she charged up switchbacks. I hugged her hard with my thighs to balance in the saddle and prayed it hadn’t slipped. My rational mind reeled over the steep exposure. I wondered how in the world we got up here above 11,000 feet.

“I couldn’t have gotten here on my own two feet”, I said out loud to no one in particular. The wind carried it back to me, and I gave Buttermilk a grateful pat on the poll.

Just a few days prior to traversing Cougar Pass, I entered into a sabbatical from work straight into the heart of the Absaroka Mountains with a diverse group of nine fellow students, three instructors (all badass women!), and a herd of 18 horses by way of Three Peaks Ranch in Wyoming. We journeyed together across the Shoshone and Bridger-Teton National Forests and Teton Wilderness, covering over 55 miles in about ten days.

These long days that began before sunrise and ended well into the dark night consisted of making camp, breaking camp, cooking for others, planning the day’s route via topographical map, packing horses, and most importantly, doing everything possible to ensure food, water, and safety for the horses.

“There are horses and there are mountain horses. Taken alone, they move your soul. Taken together, they move your life.”

–Tom Reed

A manty tarp spread wide like a dinner table and a WhisperLite camp stove whirring to life provided the environment the humans needed to get to know one another, our backstories and beyond. I was asked about my family at our first breakfast.

A split in the trail. Go left and stay armored, protected, safe. Go right to dive in to the pool of uncertainty, caring, not careful.

I delved into my relationship with my siblings — who I grew up with and who I didn’t — how I sought out and met my older sister when I was 16, how I wasn’t brave enough to ever visit my brother’s grave until I was in my late twenties, and how being out in the wilderness with horses reminded me of my parents. In return, she shared about her mother’s failing health and the sacrifices she’d made to care for her.

Countless hours spent sharing around manty tarps, in tents, and on trails knit us together. I witnessed reciprocated vulnerability be a catalyst for trust, belonging, and mutual respect. There’s magic in listening and presence that makes us feel safe enough to share ourselves, and there’s sacredness in holding and handling another’s story with great care. It’s the branding of meaningful connection.

While I learned to rely on my team, I noticed shifts in understanding of myself in this new environment. Before my trip, I’d been seriously struggling with boundaries around rest. The ancient part of me that has always had something to prove to be “enough” had been keeping a lot of plates spinning in life at home. While trying to be enough for everyone else, I was often overwhelmed and burned out. I knew if I was going to live with a shred of integrity on this expedition, I’d have to communicate (and practice keeping) intentional boundaries around rest and work.

_____

Solitude. Silence. Stillness.

They’re vital for my well-being, but stepping toward my new teammates with this vulnerable truth felt scary and risky. Would they honor my boundaries? Could I? Can they see through my need to be needed and just let me be when I needed that more? I’d hate to be perceived as lazy or incompetent, or come to find that my presence didn’t matter anyway. It’s the path of least resistance for me to hustle and perform all the damn time, but I knew it would be foolish to attempt that out there.

I let my team know when I wanted to cook and take on the heaviest of tasks, which was when I had the most energy. I didn’t get up earlier in the mornings than I had to, and I didn’t hang around chatting in the late afternoons before the rush of evening chores. They knew I was refueling and re-energizing my body and spirit. They knew where to find me.

“To be human is a constant pulling of our desire to be witnessed with the tug of our fear that no one will want us.”

–Jennifer Pastiloff

On our first night in the field, we got to camp late and I was on cooking duty for dinner. The sun was fading fast as we tied up our horses, unloaded and untacked them, and got them hobbled and ready to be put out to pasture for the night.

Just as the sun dipped below the horizon, I collected my stove and rations from inside the bear fence, and flung a manty tarp into the air to lay down a place to cook. I’d go find my tack pile and grab a headlamp and warm outer layer before it got too hard to navigate the tall grass in the dark... right after I got the water boiling.

The herd of hobbled, clumsy horses bounded by within a few feet of my tarp. I felt small, unsafe, and incredibly vulnerable — the horses were way too close for comfort, and they’re easily spooked in the dark. I knew I needed help, and I didn’t know how to get it. I kept shoo-ing them off and was growing frustrated the water was barely hot after more than 20 minutes. At the high elevation, water took a while to rapid boil, which is required to purify the water for consumption. I couldn’t leave my kitchen with the horses inching nearer to the stove, and I was almost out of light. I was way too underdressed. My wet hands were freezing. I could barely see as it was, and the faint twilight would be gone in minutes.

As my desperation peaked, I was relieved by a hungry teammate to run and grab the gear I needed to limp along to the completion of my cooking duties. My crew eventually stomached the simplistic meal of rice and beans as I considered how grossly unprepared I was to cook in those conditions or even dress myself appropriately. Not to mention, I was acutely scared of horses all over again. Their spookiness terrified me. So did mine. It was the first evening and we had a long, long way to go. I felt myself splitting, forming the containers I’d need to create a sense of safety and security for myself. With them and the desire to leave more than I took, I could perform well to serve externally, and internally shove down the feelings of incompetence, failure, and fear of not belonging.

Not enough. Not enough. Not enough.

Despite the risk of being misunderstood, I shared these fears the next morning with my team and readied myself to feel exposed and examined while I fumbled through being an absolute beginner. Sage advice from others reminded me I’d overcome extremely challenging circumstance and really took one for the team — a team of absolute beginners. We’d actually learned from then on how to improve our cooking efficiency (wear a headlamp, bring extra layers, and know that water boils quickly when covered, the flame protected from wind, and the liquid fuel canister pumped to maximum pressure. Also, be willing to ask for help before you’re in crisis.) She spoke straight to my loud inner critic: I was being too hard on myself. Maybe she was right.

Despite the rocky start, I’d earn a reputation for my culinary achievements. I became a pro at whipping up (with ease) delicious dishes like Frito pie and backcountry “dump cake” (both of which earned honorable mentions during my graduation ceremony), along with the acknowledgement that being a vulnerable leader repeatedly had a positive impact on our group.

_____

A stripped down material existence highlights the fragility of our bodies and egos. We are resilient and strong, but snowy alpine weather is too cold for comfort even with all of my layers on.

When I unloaded my horses at the end of a long day’s ride, my focus would shift from my tired, aching body to the well-being of our herd. Though it was hard to rub in a saddle all day, my horses carried my rations, my warm sleeping bag and tent, our first aid kits, and everything else needed to survive. My horses also carried their own tack and gear. They willingly stood so I could practice lash lines and securing panniers until I got it right. They knew we belonged to each other, and they reminded me again and again of this.

Learning to find a way through together collectively was the way out when we were repeatedly blindsided by vulnerability: to the elements, to the terrain, to consequential decisions. Vulnerable in new relationships with people and horses. Vulnerable as my body chafed raw on miles in a saddle, and when fetching our herd that wandered overnight irritated my chronic plantar fasciitis in cowgirl boots, and when a severe allergy attack threw me into a significant breakdown.

The hard work of it all cracked us open and built us back up into more resilient, interdependent people. Unearthing our vulnerabilities and widening our window of tolerance grew us every single day. I didn’t simply hack it out in the backcountry, I thrived. Choosing vulnerability again and again allowed me to live undivided with integrity. It was the trail that led to meaningful human experiences within myself, with others, and with my horses Buttermilk, Macho, and Doug. It was the way a team could grow from strangers to… not really strangers at all.

While making everyone else in the world happy, hustling for “enough” made me miserable and sick. When the trying so hard left, I was exposed, sober, and vulnerable. It wasn’t horses or cooking or people that scared me. It ultimately was my own vulnerability, honesty, and needs that scared me.

It was how deeply I’d forgotten myself that scared me.

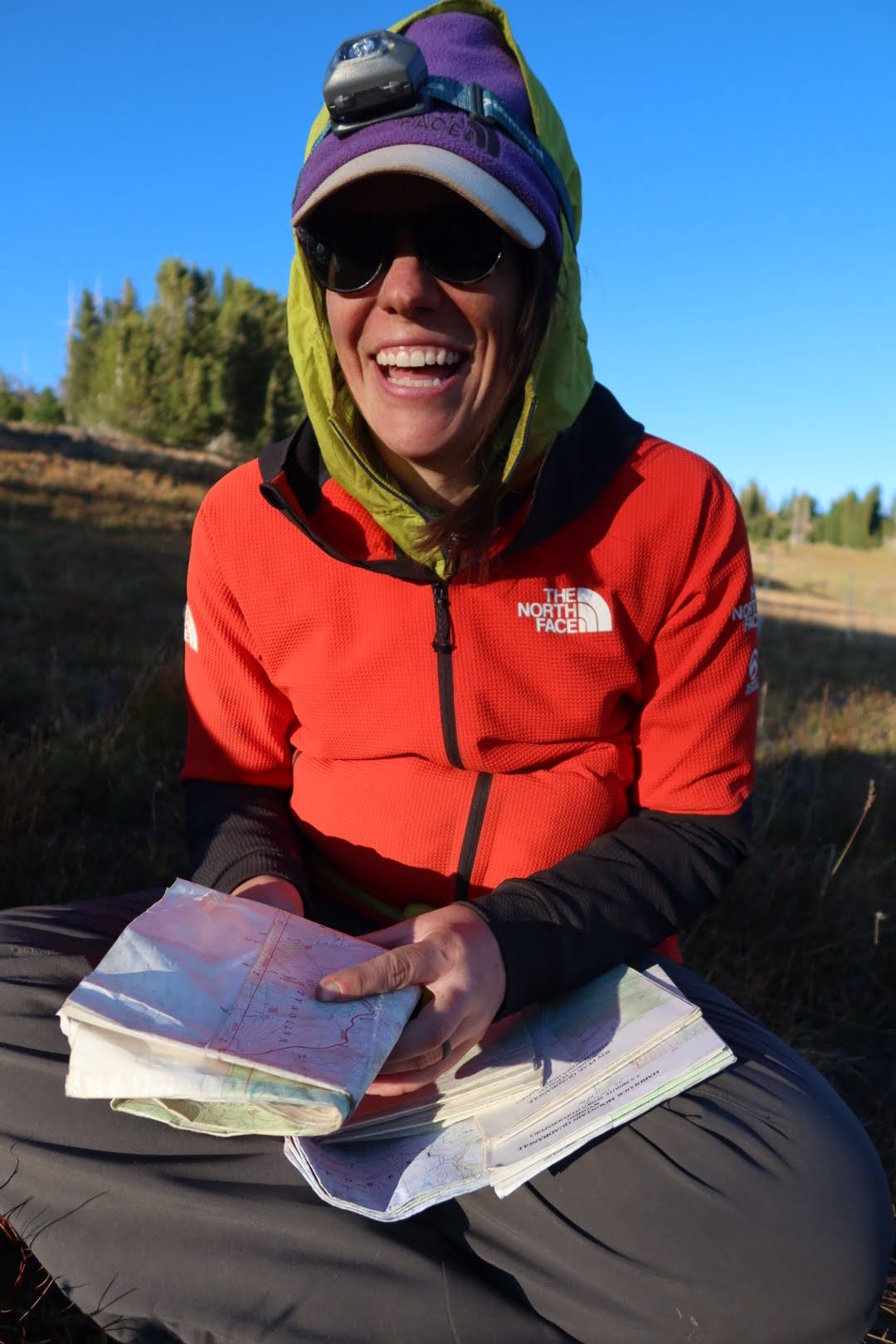

The scariness began to fade as others met me where I was, which wasn’t at the mythical center of keeping it all together. When I’d roll off my camp mat, pull on my striped mud boots and beacon-bright red soft shell jacket, and stumble out of my tent into the foggy mornings, I was often handed a hot thermos of coffee and someone’s own precious Crazy Creek chair that said to me, “I see you, and you are enough.”

It took the ritual of “I see you” coffee morning after early morning to allow myself to believe they didn’t expect me to work myself to death meeting their needs while ignoring my own, and that maybe I didn’t have to either. That I could just be sometimes.

_____

"Vulnerability is the core, the heart, the center, of meaningful human experiences."

–Brené Brown

This time in wilderness at a crossroads in my life asked me to confront ideas and realities that are painful and beautiful and tender and sacred. Traversing deep wilderness is more than a challenge and an escape: it’s an awakening. I began the course ready to unplug and learn new skills for two weeks in the midst of massive upheaval in my life. I left it having gathered more about being human: the essential staples of connection, interdependence, reverence, belonging, and wild vulnerability. I am conscious of and humbled how we carry each other to places we can’t get on our own two feet.

I’m grateful for how my horses and team helped carry me until I was ready to begin unpacking this, like the way my parents, my siblings, my husband, and people of my past and present have carried me into a life where I’m free to wrestle my own vulnerabilities into strengths as I’m wandering home. And, along the way, taking invitations to connect with horses and mountains and a Corn Moon, which I’ve learned is a lot like connecting to my soul. Maybe that can just be enough.

It’s vulnerability that attracts meaningful human experiences that “careful” and “safe” rarely do. It beckons us deeper into the wilderness. It reminds us what “enough” truly is. Even so, I wonder what my horses, the land, my team, my people, and I might still have to teach each other. I wonder if we ever forgot to set that electric bear fence. And I still wonder, always, what meaningful human experiences lie ahead.

I am changed. I am full. I am trying to live with vulnerability and connection at my core, my heart, my center as the gap continues to increase between the wilderness and my home life. Some days I am like a beginner. But even then, I am enough.

Dreaming of summer adventures,

"Choosing vulnerability again and again allowed me to live undivided with integrity." WOW that spoke directly to my soul. Thank you for your gift of words to share your experience. I'm grateful.

This is so beautiful! Thank you for sharing!!