I’ve told this story on Wandering Home before, but it’s time to tell it again:

Art is my native tongue. My heart language.

I've always been an artist. I studied and made art for any project possible in elementary school. I designed and edited the high school year book and newspaper. I formed an art club in high school. I “lettered” in art, you know, like for a varsity jacket I never owned. It was my whole world.

For college, I went to art school to get my BFA. I found I felt very at home in a classroom where students pick at paint under their nails while a professor asks for contemplation on the social importance of a Gordon Parks or a Cindy Sherman.

Production and commercial art have dominated my last decade-plus of life for the sake of making a living while making an impact, but I didn’t stop trying to get back in the studio. I pulled out the paints and brushes every once in a while, and I took a printmaking class at the San Antonio School of Art years ago, and a semester-long photography course at Community College of Aurora more recently.

Each time I learned a new medium, it grew my ability to communicate, to express myself and my thoughts. Especially with photography. That really felt like getting a grasp on a new language, a dialect of my native tongue I appreciated and could comprehend, but couldn't write or speak myself. I loved growing a language competency that allowed me to say what I meant with a camera in ways I can't with other mediums.

Along the way, I’ve learned to use my work as a tool to say what's important. It explains why Banksy and Shirin Neshat and Barbara Kruger and Shepard Fairey are my art heroes. They know how to say what’s important, but they tell it powerfully. Beautifully. Effectively.

Art as resistance is my favorite kind of art. I don't know a better way to do it.

This goes way back for me—this elixir of art as resistance.

Every year in my high school art class, students were invited to participate in a patriotic art contest juried by the Ladies Auxiliary VFW. One year, eager to bag an easy win, I painted a bald eagle in front of the stripes on an American flag. It swept the VFW contest and my high school student show awards.

I was good with acrylics, but even more so, I played the audience. I’d understood the assignment. I already understood brand messaging. It was the VFW in rural Missouri. Of course an eagle and Old Glory would win. I overheard a man at my student art show say, “It doesn’t get any more American than that” as he stood proud before my painting. I can only assume he cast his vote on my behalf.

I realized I’d rigged the show. It was too easy.

The following year when the opportunity came back around, I decided I would push the bounds a bit. I didn’t know how, because I still definitely wanted to win, but I’d have to rely on my artist’s intuition to guide me to the right image.

The all-American symbols were too on the nose. Boring, actually. If I was going to enter the contest again, I wanted to win because the art I made was both technically great and conceptually interesting. I wanted to make a statement or raise awareness to something other than how well I’m able to conceive a visual story that satisfies only the most basic requirements.

I was scouring the stacks of reference magazines in search of a better story to tell when I came across a 2007 issue of Marines Magazine. The feature article covered Code Talkers, the Navajo Marines who, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, spoke Navajo to the elusion of the Japanese intercepting U.S. radio messages and transmissions. The Navajo Marines were of vital importance to the mission. The Navajo language was mastered only by the Navajo themselves, and interpreted only with Navajo ears. No one could de-code it. Their language was indecipherable to the Japanese.

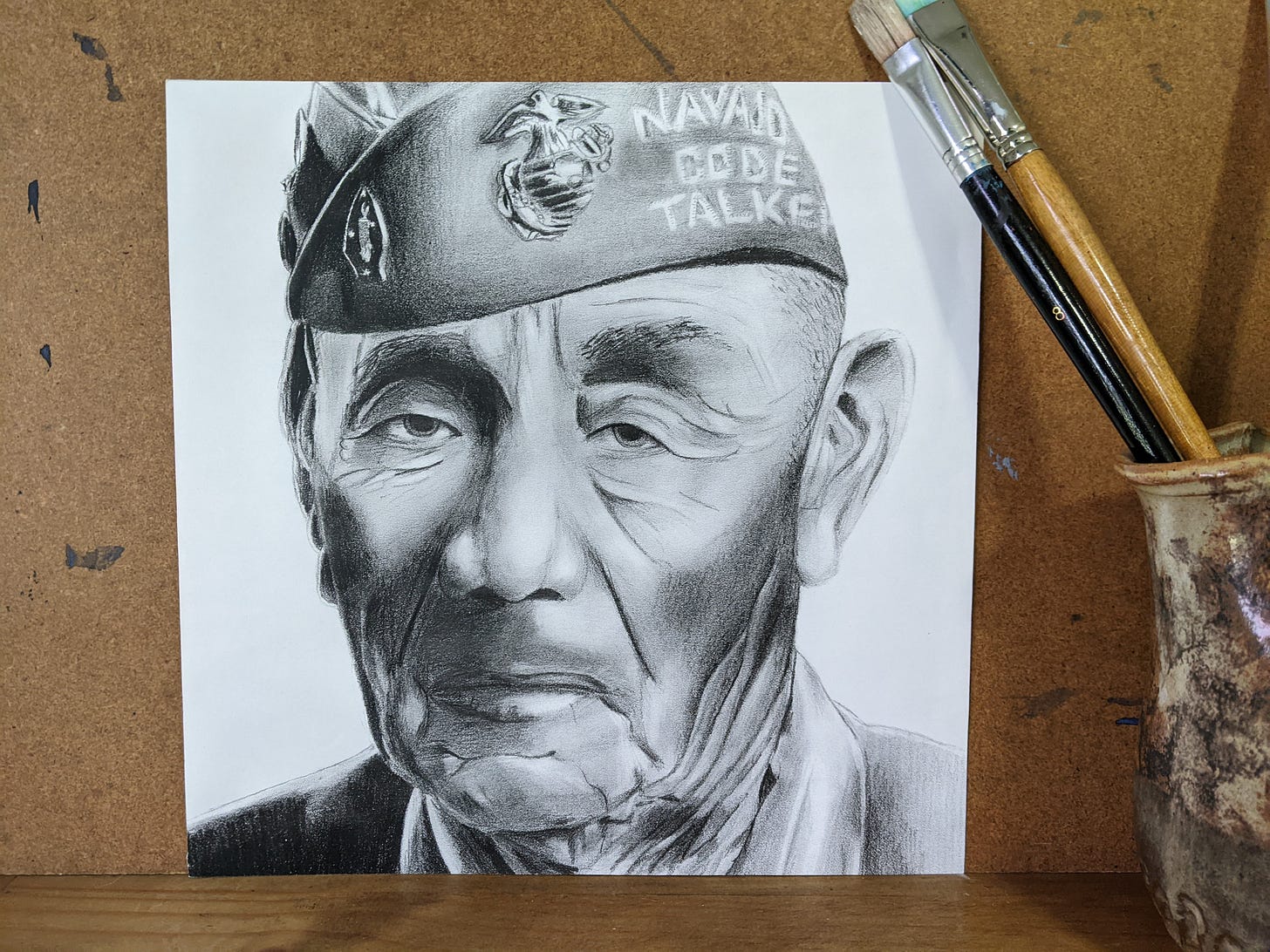

The article highlighted several Navajo men. One of them was Pvt. George B. Willie, Sr., then 81 years old. He’d served with the 2nd Marine Division at Guadalcanal and Okinawa from 1942-1945. The portrait of Pvt. Willie was compelling. Dramatic, even. His Marines eagle, globe, and anchor emblem was spit shined. His aged cover had “Navajo Code Talkers” stitched onto the side. At 81 years old, his wrinkles were prominent, deep crevasses across his face and neck. His eyes were tired.

I drew the portrait in graphite, taking special care with his expression. I wanted his life to shine through.

I got to present the final work in the local VFW contest. Normally in an artist talk, I’d share about the drawing process or how I made something, but this time, I decided to tell about the work the Navajo Code Talkers did in WWII. How, in their heart language, in their native tongue, their unique skills and willingness to serve changed the course of history. How the Indigenous American experience contributed to this effort on behalf of all who live in the United States.

How I don’t think it gets more American than that.

I got an extra print made of the drawing to try to send to George’s family. I wasn’t able to locate him personally, but I found via Google he had a daughter in Arizona, and I tracked down her email address. I wrote her this email:

”Annabelle,

I have a print of drawing I'd like to gift to you and your family. In 2008, I entered a Young American Patriotic Art Contest sponsored by Ladies Auxiliary VFW and won multiple awards for my submission. The drawing is a portrait of your father based on a photograph portrait of him in Marines Magazine in 2007. The original was purchased in 2008 and has since hung in VFW Post 2654 in Moberly, Missouri.Please let me know if you are willing to receive the framed print by mail or alternate method.

Thanks,

Shelby”

She wrote back:

”Hi Shelby,

Great news you have a portrait of our father! Wow! So there's a pic at VFW Post in Moberly, Missouri? That is wonderful!

Yes, my parents and family would appreciate our dad receiving the framed picture.

Thanks,

Annabelle”

I sent her the print. She said her school, where she works as a Navajo Language Instructor, would be honoring her father soon. She said she would present him with the framed picture I sent in front of students, parents, and staff. She wanted it to be special, and to let them know I made the drawing honoring her father.

I was bowled over that she made a big deal of the presentation of it. That I had been able to honor his story, both to his family and my own community. That I was able to transcend the expectations of making art that’s just aesthetic or obvious. That I got to be a small part of his story before he died in his 90’s in Arizona in 2017.

My art meant something to a lot of people. That matters so much more to me than the multiple awards I earned, or the scholarship money I won, or that I’d sold the original drawing to the VFW for actual money—my first ever art sale.

That’s when it clicked for me: Art can be a real weapon.

Since my experience sharing Pvt. Wille’s story, I've discovered a magic to showing up to a photo shoot or a blank canvas or empty page with the intent to practice storytelling, to embody activism. I get to use art to push thoughts, ideas, and possibility forward in the world. I get to explore how art helps us change and ask what it means to be human. I get to be a bridge to people telling their stories the way they want them told, and to communities often ignored or even silenced.

Recently my friend and teacher, Kirbee Miller, asked me what I’m afraid of? I responded with: meaninglessness. In life, in work, in art, in relationships – all of it. Give me meaning or give me death. It’s dramatic, but it’s true. I’m afraid of the things I make or say or do to be meaningless. I don’t think they are meaningless because I seek to infuse everything I do with meaning, impact, and sacramentality. But I’m still aware, intentional, and afraid anyway.

I resist this fear by making art as resistance.

I combat this fear by using art as a weapon.

I’ve had the opportunity to make meaning from Colorado to the Middle East for many years now as a designer, photographer, writer, and artist.

I still believe there’s nothing wrong with art only for the sake of beauty or art only for the sake of meaning. It’s just that I prefer both. The elixir for me—where I’m sure I’m doing what I’m made to do and I'm most sure of the purpose of this creative gift—is to make peace, seek truth, hunt beauty, find hope.

I relaunched my Etsy store to fundraise for my June trip to Lebanon and Jordan to volunteer as a photographer for Beirut and Beyond and their partners in Palestinian refugee camps. I share more about the trip and work in this post.

Here are some details about my shop:

The ShelbyMathisStudios Shop is open through May 12.

It's all original photography made in the spirit of impact.

The profits I make will support my 2 week trip to the Middle East in June.

This is a volunteer trip, and though I donate my time, skills, and art, I still have to get there and have trip expenses for the time I’m working. Your support means we get to do it together.

This sale keeps me creating and working, which is essential to me and those I partner with. I like to think asking for help with this sort of thing is art as resistance too.

It's resistance to make art that helps us lean in to new or hard conversations.

It’s resistance to make art I can’t guarantee people will love to tell the stories untold.

It’s resistance to elevate the voices of Palestinian refugees.

It’s resistance to believe my art can fight oppression.

It’s resistance, for me, to be an artist in the first place.

It’s resistance to use art as a weapon.

It’s resistance to use it for good.

Resist with me?

You are an absolute wonder, Shelby, and I count myself lucky to know you. This is absolutely beautiful, just like you. Thank you for sharing your process, your passion, and your heart. Love you!